101. You and Your Career: Hamming’s crash-course on career success

success research teaching amir_shahmoradi ideas

Reference: 101. You and Your Career: Hamming’s crash-course on career success

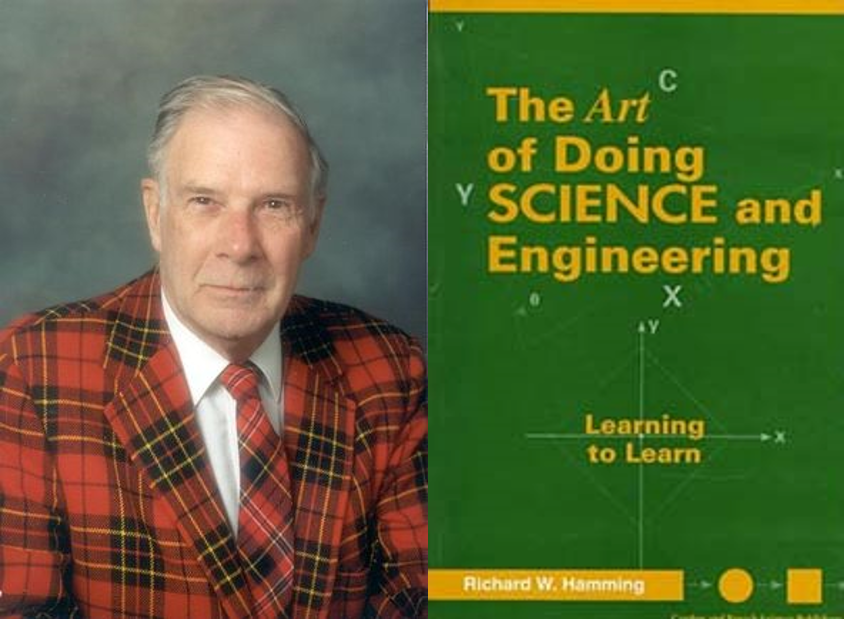

Recently, it came to my attention that February 11, 2016, marks the 101st anniversary of the birth of Richard W. Hamming, a well-known mathematician and computer scientist of the 20th century. As a researcher who has always sought career advice from great minds, I have found Hamming’s book on The Art of Doing Science and Engineering: Learning to Learn an enlightening read that helped me improve my daily scientific and personal life. This coincidence in time prompted me to revise and improve my summary of Hamming’s advice on career success, have it reviewed and criticized by two senior highly successful scientists, and write in the form of a concise, readable essay for those interested. There are likely many young researchers and graduate students, like myself, who are very enthusiastic and receptive to career advice from one of the greatest minds of the 20th century.

The essay focuses on advice for career success by Richard W. Hamming. Unlike the scientific works of Hamming, his valuable thoughts and advice on the art of doing scientific research and achieving career success have been relatively less recognized and appreciated. Hamming summarized his personal experience and ideas in his book titled “The Art of Doing Science and Engineering: Learning to Learn” in his final years. In his book, Hamming provides valuable practical lessons on how to excel in research and career, based on his own lifelong scientific career experience and his close friendship and collaboration with some of the greatest minds of the 20th century, such as Claude Shannon and Nobel laureate Richard Feynman.

What is success?

Why do so few scientists become so famous for their achievements? One thing is known for sure; once famous, it is relatively easy to remain or become more famous. But what does it take to become famous or to do great work? What is the difference between the very capable people and those who do not contribute significantly to the advancement of science? Is there a broad set of principles that everyone could use to achieve career success?

February 11th, 2016, marked the 101st anniversary of the birth of Richard W. Hamming. A well-known and prolific mathematician and computer scientist, Hamming believed that success and successful people come in many forms and flavors. However, despite the apparent great variety on the surface, there are many common elements and traits underlying their success. Hamming spent the last two decades of his life at the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California, focusing mostly on education. There he held a series of lectures on the definition and the art of doing significant research and summarized them in his book titled “The Art of Doing Science and Engineering: Learning to Learn” [1]. The essence of the book, according to Hamming himself, is one sentence: “Success is to do the right thing, at the right time, in the right way”. Leaving the context for success to the reader, Hamming signifies and explains the approach and “style” that can lead to success which, he argues, are remarkably similar among most professions and careers.

Hamming’s advice on career success could be summarized by three steps:

- overcoming the psychological barriers to success,

- developing a long-term vision, and

- adopting a style of work and life that leads to success. The following is an attempt to highlight the key elements in each of the three steps.

1. Overcoming the psychological barriers to success

Luck favors the prepared mind (Louis Pasteur).

One major objection cited against striving to do great things is the belief that success is all a matter of luck. While there is sometimes an element of luck involved in success, it is in no way necessary or sufficient to bring sustained success. According to Hamming, you prepare yourself to succeed or not by your daily lifestyle, and when luck hits you, you are either prepared to take advantage or not.

Genius is 99% perspiration and 1% inspiration (Thomas Edison).

Exceptional talent is another major criterion that is often deemed necessary for success. Yet, Isaac Newton, arguably the greatest natural scientist in history [2], observed that if others would think as hard as he did, they would be able to make the same discoveries. To a great extent, it is constant hard work applied over many years that can lead to creative acts. The very able people work very hard, all the time. High IQ may be a help but is not a necessity for success.

Confidence and courage are essential components of success.

There is an old saying that “a prophet is without honor in his own nation” [3]. Great people often face opposition on their way. However, an important common trait of them is courage and self-confidence in that they can do great work. There is, of course, a fine line between overconfidence and lack of confidence. Lack of confidence often leads to abandoning a good idea too soon, and overconfidence often results in sticking to a bad idea too long. The courage to continue is also essential since great research often has long periods with no success and many discouragements.

2. Developing a long-term vision for success

Achieving success requires working on important problems.

According to Hamming, direct observation and direct questioning of people show that most scientists spend most of their time working on problems they believe are not important nor are likely to lead to anything important. “If what you are working on is not important and not likely to lead to important things, then why are you working on it?” Hamming recalls changing the career track of a fellow chemist by asking him this simple question during a daily lunch gathering.

The importance of a problem is in its solvability.

An important problem is one that can be approached and attacked, not necessarily a problem with the greatest inherent consequences. There are many problems whose solutions can have real implications for humanity, such as time travel. However, according to Hamming, so long as there is no way of approaching them, they are not considered important. Sometimes problems that are not considered important will become important in the future. The art of success is to identify and approach these problems in advance. Great people often have multiple problems in mind that they consider of great importance. Once they find a clue to solve one, they drop other ideas to work on it immediately.

Desire to do excellent work is a key trait for success.

A person without a goal tends to wander like a drunken sailor; every step goes in one direction and tends to cancel the previous steps. With a vision of excellence and with the goal of doing significant work, there is the tendency for the steps to go in the same direction. As Hamming repeatedly emphasizes in his book, the difference between having a vision and not having a vision is almost everything, and doing excellent work provides a steady goal in this world of constant change.

3. Adopting the right style for success

Progress is impossible without change.

Not every change leads to progress, but progress requires change. New ideas are often resisted by people or the establishment. Successful people embrace change and are receptive to new ideas, tools, and arrangements.

Great people tolerate ambiguity.

They can have varying degrees of certainty about different things but are not absolutely sure of anything. This is a necessary trait for success. Too much belief in some ideas, research or some organization will obscure the chances of significant improvements.

Defects can often be inverted to career assets.

When stuck, inverting and reformulating the problem can often lead to a significant step forward: In the early years of computer development, programming had to be done by large collaborative efforts of many programmers in an absolute binary numeral system. As an employee of Bell Laboratories in the 1950s, Hamming knew he would not be given an “acre of programmers” to do programming for him. After a few weeks of pondering potential resolutions, he decided to develop a programming language that would handle details of tedious binary coding for him instead of hiring binary programmers. By simply inverting the problem, Hamming was directly led to the frontier of computer science at the time and developed the L2 programming language, one of the earliest computer languages, in 1956. Of course, not all blockages can be so rearranged. But those that can be reformulated can sometimes lead to revolutionary discoveries that open new fields of science.

Keeping the right vision requires thinking out of the box regularly.

Most people immerse themselves in the sea of details almost all the time. Achieving success requires coming out of details frequently, on a regular basis for many years, to look at the bigger picture. One way to do this is to set aside a few hours per week, as much as 10% of the weekly working hours, for “great thoughts” and careful examination of trends and important questions in the field. Hamming recommends setting aside Friday afternoons for such thoughts since distractions and work stresses are minimal.

Open doors often lead to open minds.

Great people frequently exchange ideas with others. Hamming specifically signifies the importance of working with office doors left open to everyone; “…those with the closed doors, while working just as hard as others, seem to work on slightly wrong problems….” Hamming recalls from his years of work at Bell laboratories; “…[and] those who have let their door stay open get less work done but tend to work on the right problems!”. He emphasizes the importance of communication and sharing ideas freely with others. Rarely he recalls his ideas being stolen by another person in his life-long career. Clinging to exclusive rights to an idea can sometimes do more harm than benefit eventually.

Good ideas must be presented well.

Many scientists think good ideas will win out automatically and need not be carefully presented. Unfortunately, many good ideas in the history of science had to be rediscovered by a different person because they were not well presented the first time, years before rediscovery. For example, many of the great works of Ernst Stueckelberg, a prominent mathematician and physicist of the 20th century, remained unrecognized for years due to his lack of contact with the scientific community. As a result, Stueckelberg did not contribute in a clearly visible way to the advancement of his field of science (the theory of elementary particles) despite his exceptionally original and novel ideas [4]. According to Hamming, selling new ideas requires mastering three forms of communication: formal presentations, written reports, and informal presentations as they happen to occur. To master the expression of ideas, Hamming suggests adopting the habit of privately critiquing the “style” of other people’s presentations, asking the opinions of others about them, and adopting those presentation styles that seem to be personally effective for better communication. This includes the gentle art of telling jokes.

Fame can be a curse to quality productivity.

The greatest works of scientists are often done early on in their careers when they did not have as many tools and freedom as they were given after becoming famous. Famous scientists tend to continue to work on the same problems which brought them fame, but which are also sometimes no longer of great importance to society. Hamming argues that this is a major threat posing sustained success.

Let success prospects shine in your work and lifestyle.

Hamming frequently cites “style” as the essence of his book and the most important feature of success; “It is not important how much you do, but how you do it” he says. He recommends adopting the philosophy of do the best I can in the given circumstances, studying more success than failure stories, adopting success elements and approaches from those who have already achieved career success, reorganizing life, and making more effective use of the time that is often wasted every day by reading irrelevant material, in front of the TV, in rush-hour traffic, and other similar situations. It is often easy to see the energy, vigor, and “the drive to do great work” in the lifestyle of successful people.

Hamming ends the last chapter of his book by asking the reader: Is the effort required for excellence worth it? He believes the chief gain is in the effort to change yourself, and it is less in the winning you might expect. A life in which you do not try to extend yourself regularly is not worth living, or as Socrates said The unexamined life is not worth living.

References

[1] R. W. Hamming, 1997, “Art of Doing Science and Engineering: Learning to Learn”. CRC Press.

[2] L. Smolin, 2006, “New Einsteins need positive environment, independent spirit”. Physics Today, 1 11, 59(11), pp. 12-14.

[3] Zondervan, 2012, “NIV, Books of the Bible”. Zondervan publishing company.

[4] J. Lacki, H. Ruegg, and G. Wanders, 2009, “E.C.G. Stueckelberg, An Unconventional Figure of Twentieth Century Physics: Selected Scientific Papers with Commentaries”. Springer Science & Business Media